Quando compro este livro, estou no aeroporto de Orio ao Serio. Obviamente, cheguei muito cedo: um pouco porque, para economizar, escolhi o último voo do dia e — com razão —ninguém sacrifica a hora do jantar para me acompanhar; um pouco porque, quando se trata de viajar, preciso estar sentada em frente ao portão pelo menos uma hora antes de ele abrir.

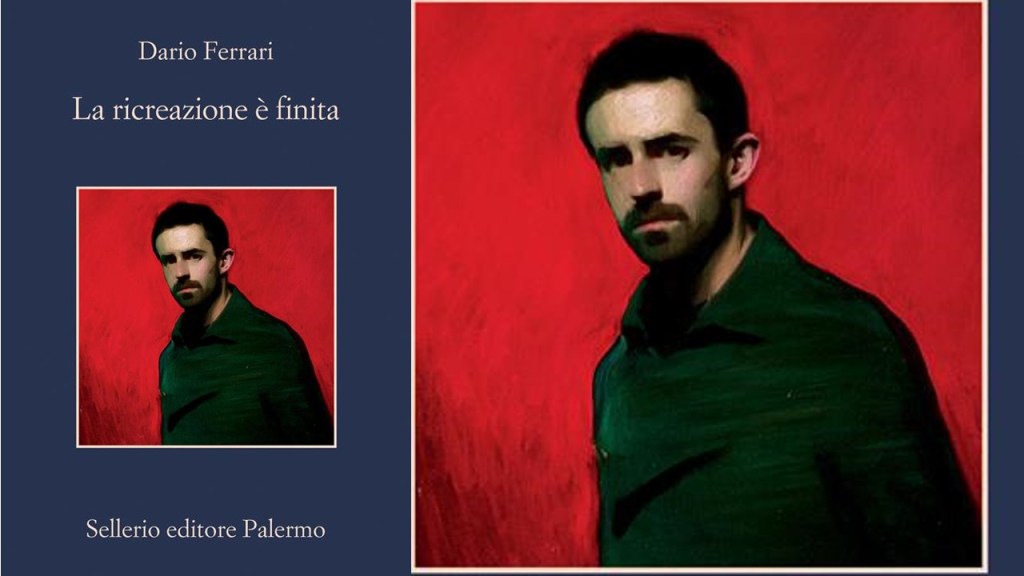

Para o caso de acontecer alguma coisa. Até agora, o máximo que aconteceu foi que o voo estava atrasado. Assim, com bastante antecedência, agarro-me à primeira solução que surge para enganar a espera: procuro um livro para comprar. Passo em revista todos os títulos até que um deles me chama particularmente a atenção.

Compro-o, ponho-o na mochila, parto e ignoro-o durante uma semana — entretanto, tenho de terminar o que estou a ler — e, finalmente, volto para casa e começo a lê-lo.

É assim que conheço Marcello, o protagonista que não quer crescer e que percebe tarde demais que se opor ao amadurecimento não o afasta disso, mas o condena a observar passivamente esse processo que se concretiza; em suma, ele não pode evitá-lo, então se limita a sofrê-lo.

Marcello, que fala em primeira pessoa, com extrema sinceridade, admite desde a primeira página que tomou todas as decisões da vida ao acaso: muito provavelmente, se as tivesse tomado cinco minutos depois, teria seguido o caminho oposto. Ele inventa algumas desculpas para se justificar um pouco — como o fato de ter lido que o sábio taoísta se deixa levar com extrema condescendência pelas circunstâncias e que, por esse motivo, ele o encarna perfeitamente —, mas depois admite que é uma justificativa de merda e continua a história.

Sem revelar muito: “por acaso”, ele ganha uma bolsa de doutorado na Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Pisa. O adjetivo foi colocado propositalmente entre aspas, mas só no final descobrimos o motivo.

No entanto, nem mesmo essa vitória o distrai da escolha casual, que acaba parecendo umanão escolha. Como diria De Andrè: “Continuarás a deixar que escolham por ti, ou finalmente escolherás?”

A partir daqui, o livro adentra-se num mundo acadêmico que permanece oculto para quem não “andares de cima” – embora reconheça que esse mundo geralmente interessa apenas a quem faz parte dele, ou seja lá em cima, mas muito mais em baixos que em outros —, atravessado por disputas internas, recomendados e apelações complicadas. Tudo sempre contado em tom irônico.

Marcello, que pela primeira vez havia escolhido responsavelmente alguns temas para seu projeto, se depara com o ilustre professor Sacrosanti, que desmonta todo o seu plano e o manda para casa com um novo projeto de pesquisa sobre Tito Stella, famoso (e fictício) terrorista de Viareggio dos anos de chumbo.Marcello não conhece Tito, mas vai conhecê-lo primeiro através das histórias de seus conhecidos e, posteriormente, graças ao corpus literário que Stella deixou, muito pouco prolífico. Tão escasso que Marcello terá que escrever sua biografia.

A partir daqui, embora o romance se passe em 2017, começa uma série de saltos temporais: avanços e retrocessos entre os ferozes anos de chumbo — dos confrontos políticos e das lutas proletárias — e um presente bem mais tranquilo.

Mas o que une as décadas é a busca obstinada por pertencimento e reconhecimento: só que não se sabe bem a quê, nem em quem. E com a diferença de que, na Itália de 1968, era inevitável estar de um lado ou de outro da barricada. Na de hoje, há tanto, tanto mesmo, por onde escolher que parece impossível, ou terrivelmente difícil, sentir-se parte de um todo. É a era do elogio à individualidade e à desunião, com o risco, como — segundo alguns — disse Lenin, de não ficar nem de um lado nem do outro, acabando por se tornar a barricada.

O livro nos conduz até o seu final através de brilhantes paralelos que levam o leitor a refletir sobre o que se perdeu e o que, ao contrário, se salvou.

Enquanto isso, as reflexões de Marcello delineiam cada vez melhor o personagem: um atrapalhado que ainda assim que age, um pessimista que não sabe manter os pés no chão, um sonhador facilmente satisfeito. Em suma, uma contradição viva e, justamente por isso, extremamente humana.

O final do livro é em parte inesperado, em parte uma evolução natural da história. Marcello, já com trinta anos, não muda radicalmente sua personalidade: ele realiza um pequeno ato, mas profundamente revolucionário para si mesmo.

Por isso, quero dizer uma coisa ao Marcello, amigo meu:

«Marcellì, porque depois de todas estas páginas, comecei a gostar de você e a compreendê-lo. Suas perturbações mentais são as mesmas que as minhas. Talvez você não seja um exemplo de determinação, mas de introspecção, sim. Talvez isso não seja suficiente para se tornar definitivamente alguém, mas servirá para alguma coisa».

Como escreveu Nayt em Poter Scegliere (Poder Escolher):

«A verdade é a minha única oferta,

você rebate que é apenas a minha,

que não sou objetivo,

que não sou gentil.

Eu respondo que, nos dias de hoje, pode-se ter adjetivos melhores

do que saber escolher, poder escolher».

Digo isso a ele, mas também a mim e a todos os Marcello que estão entre vocês: porque, embora o recreio tenha acabado, ainda temos muitas pausas pela frente para parar e descansar, olhar para dentro de nós mesmos, nos aceitar — por mais desajustados quesejamos — e seguir em frente.

Boas escolhas. Ponderadas ou instintivas, certas ou erradas que sejam.

Between Chance and Fate: Why Choosing Is the Hardest Revolution

When I buy this book, I’m at the Orio al Serio airport. Obviously, I’m way too early: partly because, to save money, I chose the last flight of the day and — quite rightly — no one is willing to sacrifice their dinner hour to drive me there; partly because, when it comes to traveling, I need to be sitting in front of the gate at least an hour before it even opens. You never know what might happen. Up to now, the worst that has occurred is that the flight was delayed.

So, very early and with nothing to do, I cling to the first solution that presents itself to kill time: I look for a book to buy.

I go through all the titles until one catches my attention in a special way. I buy it, slip it into my backpack, take off, and ignore it for a week — in the meantime I have to finish the book I’m currently reading — then I finally get back home and start reading it.

That’s how I meet Marcello, the protagonist who has no desire to grow up and realizes too late that resisting adulthood doesn’t keep him from becoming an adult; it merely condemns him to passively observe the process as it unfolds. In other words, he can’t avoid it, so he simply endures it.

Marcello, speaking in the first person with utmost sincerity, admits from the very first page that every life choice he has made was random: most likely, if he had made them five minutes later, he would have taken the opposite path. He throws out a couple of excuses to justify himself a bit — like having read that the Taoist sage lets himself be carried along by circumstances with extreme compliance and that, for this reason, Marcello embodies him perfectly — but then he admits that it’s a bullshit justification and carries on with his story.

Without revealing too much: he “randomly” wins a PhD scholarship at the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Pisa. The adjective in quotes is intentional, but the reason for that is discovered only at the end.

However, not even this success distracts him from his habit of random choices, which ultimately seems more like a non-choice. As De André would say: “Will you keep letting yourself be chosen, or will you finally choose?”

From there, the book dives into an academic world that stays hidden from those who don’t frequent the “upper floors” — while acknowledging that this world generally interests only those who are part of it; upper floors, yes, but much lower than others — a world marked by internal feuds, favoritism, and complicated titles. All narrated in an ironic tone.

Marcello, who for once had responsibly chosen some topics for his project, finds himself in front of the illustrious Professor Sacrosanti, who dismantles his entire plan and sends him home with a new research project on Tito Stella, a famous (and fictional) terrorist from Viareggio during the Years of Lead.

Marcello doesn’t know who he is, but he will learn first through anecdotes from acquaintances, and then through the literary corpus Stella left behind — very small indeed. So small that Marcello will eventually have to write his biography himself.

From here, although the novel is set in 2017, a series of temporal jumps begin: back and forth between the violent Years of Lead — full of political clashes and proletarian struggles — and a much more relaxed present.

But uniting the decades is the stubborn search for belonging and recognition: except no one really knows belonging to what, or recognition from whom. With the difference that in Italy in 1968 it was inevitable to stand on one side or the other of the barricade. Today, there is so much — too much — to choose from that it seems impossible, or terribly difficult, to feel part of anything. It’s the age that celebrates individuality and fragmentation, with the risk, as Lenin reportedly said, of standing neither on one side nor the other, ending up becoming the barricade itself.

The book leads us to its end through brilliant parallels that push the reader to reflect on what has been lost and what has instead been preserved.

Meanwhile, Marcello’s reflections outline his character more clearly: a scatterbrain who acts anyway, a pessimist who can’t keep his feet on the ground, an easily pleased dreamer. In short, a living contradiction — and precisely for this reason, deeply human.

The ending of the book is partly unexpected, partly a natural evolution of the story. Marcello, already in his thirties, does not revolutionize himself: he takes a small action, but one that is profoundly revolutionary for him.

For this reason, there’s one thing I want to tell Marcello, my dear friend:

“Marcellì, because after all these pages I’ve even grown fond of you, and I get you. Your mental turmoil is the same as mine. Maybe you’re not the champion of decisiveness, but you’re certainly good at looking inside yourself. Maybe that’s not enough to finally become someone, but surely it’s worth something.”

As Nayt wrote in Poter Scegliere:

Truth is my only offering,

you reply that it’s only mine,

that I’m not objective,

that I’m not kind.

I answer that, in these times,

there are better adjectives to have

than knowing how to choose, than being able to choose.

I say it to him, but also to myself and to all the Marcellos among you: because although recess is over, there are still many breaks ahead of us, to stop and rest, to look within ourselves, to accept ourselves — the messes that we are — and move forward.

Good choices. Thought-out or instinctive, right or wrong as they may be.

Leave a comment